Contact Us | 1.800.2.BERLIN

Unlocking the Power of Package Design: Building a Business Case

Design innovation evangelists can finally take a well-deserved breather. There is no shortage of examples describing how design can resurrect once-troubled firms such as Apple and elevate others such as LG and Samsung to premium status. Brands like Method, with its category-busting aesthetic, leapt straight onto the big grid of home and personal-care products. And juggernauts like P&G have used product and package innovation to reinforce their leadership role in categories from razors to detergent. There remains very little debate on design’s criticality, especially within the world of consumer goods.

While we can all appreciate a “good” or “well designed” package when we see it on the cover of Business Week, it’s harder to know “how good is it?”, “is it good enough?”, and “is it worth it?” before making the investment.

This last question – “Is it worth it?” – is the focus of this paper. All too often, package design innovations fail to see the light of day not because they lack shelf impact or functionality, but because their sponsors lack the tools or understanding to fully frame the benefits a new package can bring in the form of lowering costs, improving efficiencies, and increasing sales.

Understanding how to frame decisions about design at the project or product level – in theory and in practice – can accelerate a brand’s growth and profitability. We will address this in three parts:

- First, by recognizing the importance of quantification when building a business case.

- Second, by identifying design-influenced value levers.

- Third, by using a simple calculator that can help elicit decision criteria and facilitate optimized choices.

Before addressing the necessity of quantification, we begin with some research that underscores the power of design.

Beyond Anecdotes: The Financial Impact of Design Innovation

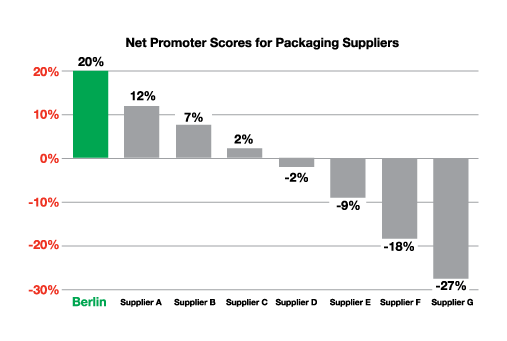

Research has shown a link between the use of design and improved business performance across key measures, including share price, profit, and market share growth.

A comprehensive study by The UK Design Council, titled The Impact of Design on Stock Market Performance, followed a group of more than 150 public companies recognized as effective users of design.

Over a 10-year span, this group of design-oriented companies out-performed the stock market indices by over 200%. From 1994 to 2004, design-oriented companies saw their stock prices appreciate over 260%, while the general stock market grew by less than 60%. This strong performance was true across industry segments and in both bull and bear markets. Indeed, the design-oriented companies saw their stocks appreciate more in bull markets and decline more slowly (or not at all) in bear markets.

Recognizing the Importance of Quantification

The discipline of package design operates alongside many other functions within a typical firm. The package designer (be it a person, a team, or an outside agency) needs to work hand-in-hand with these other functions to effect change. Efficient and profitable custom packaging programs demand that all players impacted by a package introduction (or change) be aligned on the strategic goals and critical actions. Furthermore, the final decision on whether to introduce new packaging will usually be made by someone other than a package designer, such as an individual who is accountable to the overall P&L.

One challenge for design innovation champions is that these other corporate functions are generally more numbers- and metrics-oriented (note the left-brain emphasis on analysis and numbers vs. the right-brain emphasis on imagination and spatial perception). Consider these scorecards used by other functions:

- Sales: revenue growth, number of customers, price realization.

- Procurement: cost per component, gross-margin percent.

- Manufacturing: line speed, uptime, scrap rate, conversion cost.

- Operations: storage cost per pallet, inventory turns, freight rates.

- Finance: capital spending, EBITDA growth, working capital levels.

To get approval and support for a custom package development project, design innovation proponents must appreciate the “quantitative world” that they need to please and build a business case that enumerates the benefits of a packaging change in the language the other stakeholders will understand: numbers.

Identifying Design-Influenced Value Levers

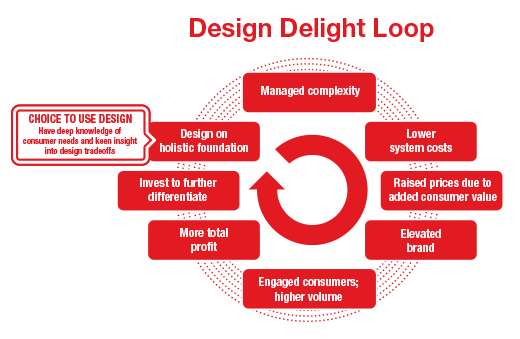

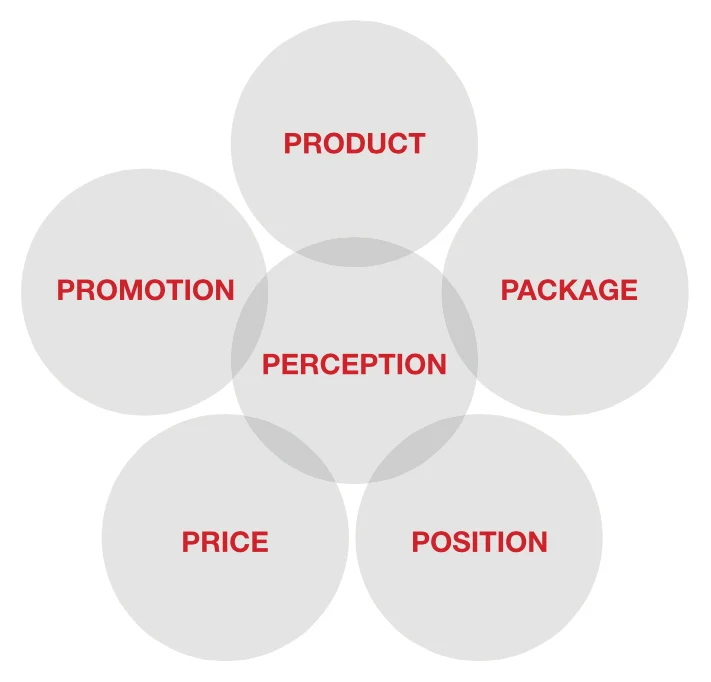

An effective package design ultimately needs to drive profit dollars to a brand. At its core, a successful package should better connect with consumers and retailers; it should make the brand more relevant. This, in turn, increases the perceived value of the total product, increasing consumer loyalty and the brand owner’s pricing power.

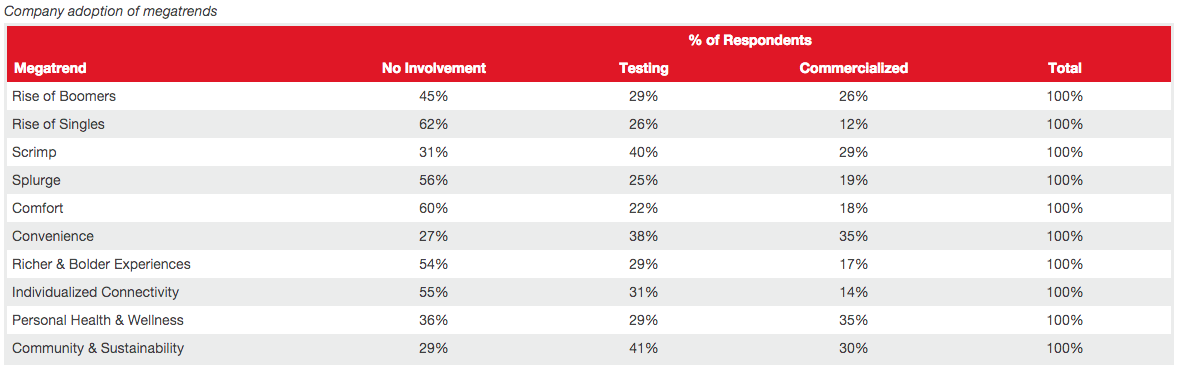

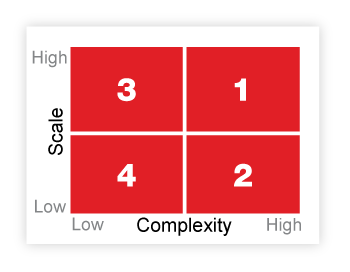

There are multiple value levers that design can influence, and all should be examined for their positive or negative effects.

Price

The everyday selling price could increase because the new design imparts a more premium image. The brand’s promotion depth or frequency could be reduced, improving the average selling price. And the retailer margin might decline as brand strength increases, unlocking higher pricing to the brand owner.

Variable Cost

Package component costs could decline if the redesign removes material or shifts spending to components with higher volumes or more competitive suppliers. The cost of the product being packaged could decline if package downsizing is incorporated into the strategy. And freight costs could decline if the pack-out efficiency improves or the redesign allows for manufacturing or filling at a location closer to the point of distribution or the end customer.

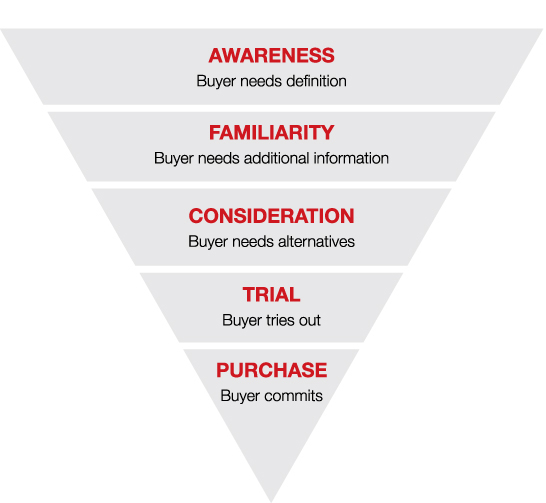

Quantity

Forecasting demand is difficult but essential. It begins with using current conditions as a base case (e.g., market share, penetration of consumer segments) and considering variables such as trial rates for new users and repeat rates (and impact on longer-term loyalty) for existing customers. An effective package redesign should improve awareness, trial, and repeat sales for a brand, driving greater overall demand.

Fixed Cost

Most package changes come with fixed or one-time costs. These can include cost of building a mold, the cost of plates for new labels, or the cost of transitioning or scrapping the old packaging stock. Not all of these costs need be borne by brand owners, who often work with their supply bases to offset one-time costs.

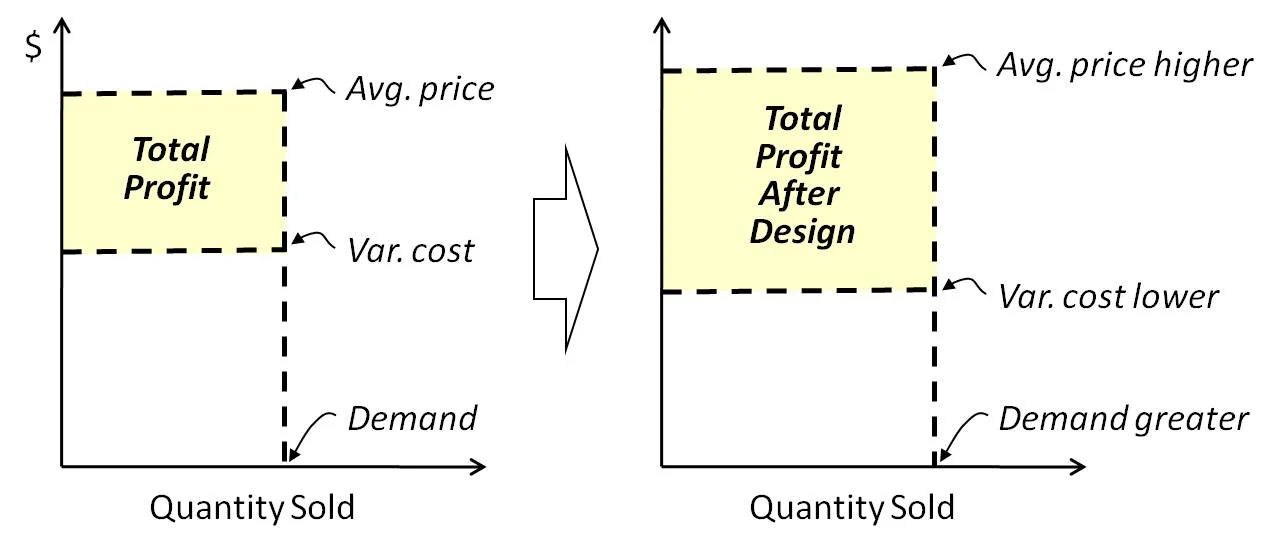

The graphic below depicts one way of visualizing these elements. On the left, we see the profit pool created today. On the right, we see a larger profit pool created by the movement of these levers.

This snapshot does not capture all the nuances of the elements highlighted above. It also does not capture the notion of time – how do these prices, costs, and quantities change this year vs. next year? Assuming that the status quo package has no “costs” may be foolish if the firm is selling less and less each year, at lower and lower prices, as consumers move away from today’s products to more relevant offerings.

Case Study: VPX Redline

VPX Redline is a super-premium line of advanced nutritional supplements designed to help consumers lose weight, build muscle, and improve focus and reaction times.

Originally packaged in aluminum cans by Vital Pharmaceuticals, Redline’s packaging was functional but expensive. In addition to the high unit costs of the container itself, VPX was saddled with high scrap rates from dented and scraped cans, either or both of which could occur at any point in the supply chain.

VPX engaged Berlin Packaging and its design division, Studio One Eleven, to analyze Redline’s packaging and to provide a solution that was functional, attractive, and profitable.

Within a matter of days, Studio One Eleven offered a PET package that was less expensive at the piece-price level without the denting and scratching issues of the outgoing container. Since the Studio designed the new container to work on the same filling equipment as the outgoing container, changeover costs were minimized and the process was quick and painless. The new container saved over $1 million in COGS in the first year.

All this was forecasted in the business case at the outset of the project, making a compelling case for redesign. In addition, consumers have great things to say about the new package. Sales of VPX Redline are up over 200% in the year since the packaging change.

Using a Simple Calculator

As noted above, the most compelling business cases show strong contrast between the economics of implementing a new package and the economics of retaining the status quo.

It’s easy to get into a complex, burdensome analysis, but we recommend starting with a simple, top-down approach. The outcome of this analysis can easily be shared with stakeholders to lay the groundwork for a more detailed business case or to identify the key areas of concern that warrant further study.

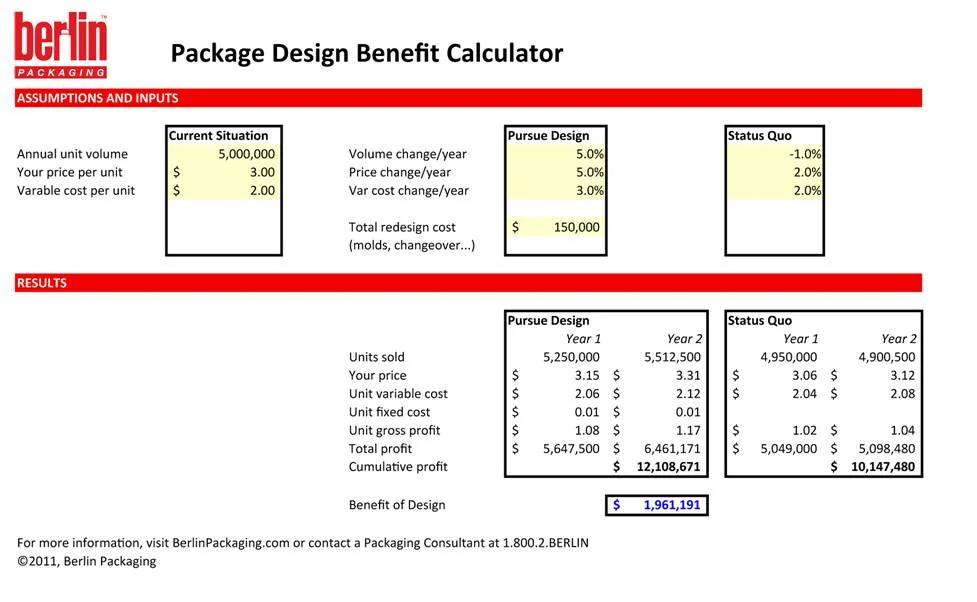

Berlin Packaging offers a Package Design Benefit Calculator to help with this step. This calculator has three key elements.

First, the user enters some data about the current situation – the annual unit volume, pricing, and variable costs.

Second, the user provides assumptions for the potential impact of a redesign on volume, price, and variable and fixed costs. They also provide this same information under the “do nothing” Status Quo scenario of retaining the current package. These assumptions are provided for each of two years.

Third, the calculator delivers the net benefit of design by comparing the “Pursue Design” economics with the “Status Quo” scenario. Sensitivities to the assumptions can easily be modeled to find break-even points below which custom development may not make sense.

A snapshot of this tool is provided below. This example models a brand that sells 5 million units annually. Over the course of two years, the assumptions suggest that a new package design will generate almost $2 million in additional profit.

This is a simple tool, but it is based on sound principles. It encourages design champions to build quantified business cases and to engage other corporate functions in discussions that will build consensus around the role that package design can have on a brand’s success.

To download a copy of this calculator (a Microsoft Excel workbook), click here or visit BerlinPackaging.com/DesignCalculator.

Getting Started

Building a business case for design innovation starts with good design solutions. The CEO and CFO will have little patience for pursuing design as an activity for its own sake; rather, it needs to be for the sake of marketplace success.

So a package designer must first uncover their consumers’ needs, their brands’ category language, and structural and graphic cues that will communicate clearly and effectively. (This, of course, is a gross simplification of the design process. The salient point is that the onus is on the designer to advocate for contextually relevant solutions.)

The next step is for the package designer to build a business case using tools such as Berlin Packaging’s Package Design Benefit Calculator.

For companies without design resources or those that wish to augment their internal team capabilities, the best design partners and agencies (like Berlin Packaging’s Studio One Eleven) can shepherd you through the innovation process and help quantify how the proposed custom solutions mesh with the business’s overall goals and objectives.

Summary

Superior design is strongly, positively correlated with business success. But all too often, companies burden design projects with all the “costs” without considering the benefits of design. This incomplete framing leads some firms to forgo innovation, leaving their products with a stagnant shelf presence and their consumers disenchanted. Indeed, innovative custom packaging can increase prices, reduce costs, and improve volume and loyalty. Employing a numbers-based business case approach to innovation advocacy is the best way to demonstrate the power of design and build support among key constituents and decision makers. Even simple tools that compare “Pursue Design” to “Status Quo” financial scenarios do much to promote discussion about how best to build successful brands and the role design innovation can play.