Contact Us | 1.800.2.BERLIN

Designing a Winning Package Structure: A Process for Delivering Delight

Package design can be a powerful differentiator and growth catalyst. But when pursued without understanding the implications of packaging change, uninformed design can lead companies down a path of value destruction. For every company that has transformed itself through smart design and branding (e.g., Target, Apple, Kia, Dyson), there are many that have wound up with egg on their faces (e.g., Tropicana’s failed 2009 rebranding). With product life cycles shrinking and shelves filled with custom designs, many marketers view inaction as a non-option and embark on “design for the sake of design” projects that fail to deliver results or even damage their brand.

As a result, if you’ve been involved with a package design process, you likely have polarized opinions about the benefit of design: either you have seen the uplift in your brand and market performance, or you have been disappointed in the experience due to the time investment, cost penalties, and consumer or retailer disengagement.

Our companion white paper, Unlocking the Power of Package Design: Building a Business Case, provides a roadmap for getting the right design projects approved. But then what? This paper is about setting up a design process for success. There are many steps to take and partners to engage; each one presents possible perils. We aim here to reduce the risk of failure.

To ensure a healthy design process, we will address four key imperatives:

- First, don’t design on a whim.

- Second, have aligned incentives.

- Third, embrace a complete, end-to-end process.

- Fourth, anticipate bottom-line results.

All of these imperatives apply when designing a package structure, and this paper focuses on structural design more so than brand strategy or graphic design. However, these imperatives can also apply to brand strategy, visual identity, decoration, and other non-structural disciplines.

Before digging into our first imperative, we will visit some of the common pitfalls that arise from packaging designed without a proper process in place.

Design Pitfalls

Every design project and product launch is filled with challenges that can wreak havoc on the outcome. Some of the most notable risks include:

- Ignoring the product category dynamics. Each category has an identifiable visual language and specific competitive dynamics. Landing too close to other brands or too far away from category signposts can confuse consumers and jeopardize your launch.

- Not capturing the consumer’s imagination and needs. A redesign that violates preferred ergonomics or is dissonant with a brand’s personality is a step backwards.

- Failing to accommodate the needs of manufacturing and operations. Without the right technical expertise, it’s easy for a package to be a logistical albatross. No matter how compelling a package concept looks on paper, the engagement is a failure if the concept doesn’t fill, take decoration, and move through the whole supply chain smoothly.

- Alienating retailers. From shelf height to facing width, retail placement constraints must be understood and adhered to. Lacking support at the shelf is a tall hurdle to overcome.

- Paying expensive fees. Six-figure invoices from design firms are commonplace. And that’s just for design sketches and maybe prototypes, not commercially-viable packaging options.

So the question is: how do you unlock the benefits of design while avoiding the landmines? Following these four imperatives can help you do both.

Don't Design on a Whim

Many of the pitfalls described above occur because the entire design endeavor is approached with the wrong mindset. Even the best companies and brand managers can be plagued by hubris that leads to shortcuts.

If you have mere opinions on consumer preferences and some ideas of design elements “that might be cool to explore” without a substantive understanding of either consumer needs or how design can fulfill them, then you are designing on a whim. This whim-based approach kicks off what we call the Design Doom Loop.

This cycle, which starts with a person designing on a whim, leads to a series of self-reinforcing consequences:

- Added complexity as products get new bells and whistles.

- Higher costs as design changes create direct and/or indirect costs through the supply chain.

- Raised prices to offset the unexpected higher costs (only rarely will someone anticipate that their redesign will lower margins).

- Damaged brand due to poor fit with consumer needs and a higher price. Disengaged consumers who vote with their wallets; instead of your product, they opt for competing products that deliver better value.

- Overall total profit declines.

- A scramble to repair the brand’s financials. “This wasn’t the intent of the redesign! We need to fix this quickly!” This scramble often leads to more shoot-from-the-hip fixes and more design-on-a-whim actions, which start the whole cycle again.

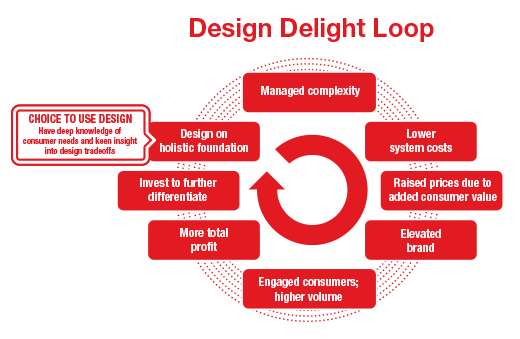

We advocate a more thoughtful approach that will instead yield a Design Delight Loop.

By starting on a firm foundation of insights around the category, the consumer, the customer, the brand, and manufacturing protocols, the design loop can be much more satisfying. Indeed, the Design Delight Loop sees:

- Complexity managed.

- Costs coming down even in light of necessary capital expenditures.

- Prices held fl at or increased to capture more of the consumer value created.

- Improved brand impression.

- More loyal and engaged consumers.

- More profit that can be returned to stakeholders or reinvested to make the product even stronger in the marketplace.

The “loop” you pursue depends very much on your mindset. But there are other factors at play that also influence the effectiveness of your design approach. We now address the dynamics of partners and process.

Have Aligned Incentives

Most companies will turn to outside support and consultants for design assistance. This makes a lot of sense for two reasons. First, design is a specific skill-set that’s often needed in sudden spurts, so having people full-time on staff doesn’t make sense for most companies. Second, the best designers get better by being exposed to many industries, situations, and brands; so the variety of a consultancy model inherently delivers better results. What’s critical, however, is that the design assistance you choose has the right incentives.

Most independent design firms charge by the hour. The more hours they invest, the more they earn. If it’s in your interest to move quickly, there are misaligned incentives with firms that sell their time.

Another solution is to work with the internal “design department” offered by package manufacturers. There are two problems here. First, these departments don’t have leading-edge creative resources. Second, the overall incentives are not well aligned. A manufacturer who owns machines is incentivized to fill capacity on those assets. Designers working in this environment will strive to give you a solution that runs on their machines rather than a solution that best meets your goals.

A better solution, regardless of the partner you choose, is to pay only if the redesign is successful. This perfectly aligns incentives, as the designer is forced to give you a solution the marketplace accepts. Very few design firms will accept these terms.

The ideal solution is to find a qualified, unbiased designer that doesn’t charge at all. We will see one example of this model later in this paper.

Embrace a Complete, End-to-End Process

With the right design resources engaged, the next step is to pursue a thorough process to uncover, refine, and execute the best design. When it relates to package structure, we recommend a six-phase approach.

Phase 0 – Pre-Design Analysis

This first phase is about research, understanding, and goals. Key elements include a complete situation assessment of the target brand’s positioning and equity, its history, its category, its competitors, and the channels it competes in. You want to learn about who the target consumer is, the way they interact with the product, and the attributes to which they assign value. No design work happens in this stage. Instead, the foundation on which design can occur is established. In addition, Phase 0’s output includes success criteria against which Phase 1 ideas will be judged.

Phase 1 – Ideation

Pen hits paper in Phase 1. Taking all the insights learned in Phase 0, this step is about exploring creative solutions. Solutions in this phase should be far-reaching and include designs with different degrees or applications of:

- Features and functionality,

- aesthetics,

- risk, and

- unit costs or system costs and investments.

Divergent thinking is the rule of the day in this phase. The output of Phase 1 consists of pages of sketches and ideas.

Phase 2 – Evaluation

In Phase 2, we pass the solutions generated in Phase 1 through the success criteria “filter” we developed in Phase 0. This Evaluation phase applies a reality check and forces tradeoffs against the goals. To ensure an efficient subsequent process, it’s critical that all stakeholders have a chance to weigh in at this stage. All parties affected by a change in packaging (or a new package) should be represented.

The output of Phase 2 consists of dimensional drawings and a list of areas for further consideration and refinement. Sometimes preliminary consumer or customer reaction can also be an outcome of this phase.

Phase 3 – Refinement

The Refinement phase involves functional or visual prototyping (rough or fancy) and consumer feedback. Manufacturing engineers should be engaged to check that the design solution is manufacturable and to weed out production surprises. Unit-cavity molds are often made to see a true representation of what the product will look like.

Up to this point, the phases can occur in sequence, but also with iteration and backtracking. If new consumer learnings arise in Refinement, for example, it might make sense to backtrack to Ideation and Evaluation. As we exit Refinement, there should be very firm confidence in the design solution.

Phase 4 – Preparation

Phase 4 is about preparing the package for implementation. Final drawings are prepared and approved, steel is cut for molds, production-tool samples are evaluated, color matches are reviewed, and testing is performed as required (e.g., drop tests or child-resistance tests).

The cooperation between design and manufacturing must be very tight at this point. Project management is an essential skill throughout the six phases, but it is mandatory at this stage. All the work that’s been put into the design is coming down the home stretch.

Phase 5 – Production

We are now in full production. The design process is not over, though, as we now listen closely to all key constituents. How is the package manufacturing and filling going? What are retailers saying? Are consumers engaging? Even when a package is in production, enhancements and tweaks can be made to maximize impact and efficiency.

These six phases may seem long and bureaucratic. They don’t need to be. What’s important is to have these phases in mind and to not skip steps as you pursue your new design.

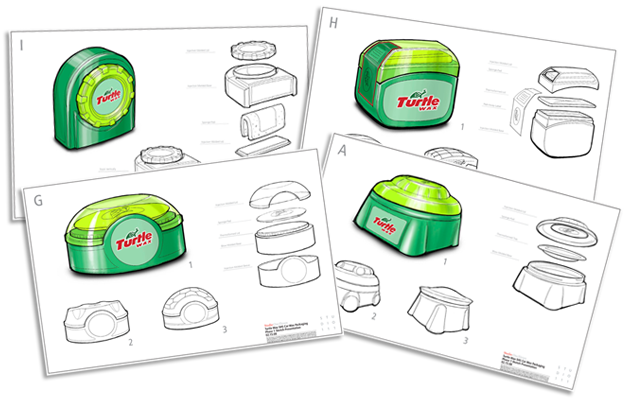

Case Study: Turtle Wax

Turtle Wax has been a global leader in car care for over 70 years. No single item in the company’s 1000+ SKU line-up was more closely associated with the brand than the iconic Super Hard Shell Paste Wax.

Although the SHS package was universally recognized, it had a history of consumer and retailer complaints and had fallen behind the times against a backdrop of competitors’ new packaging.

Turtle Wax engaged Berlin Packaging’s Studio One Eleven division to assist them in contemporizing and improving the functionality of the SHS package without losing any of the equity the brand has in the market.

Following is a quick illustration of each of the six design phases.

Phase 0 – Pre-Design Analysis

An in-depth review of the car care category and paste wax competitive landscape was conducted, including consumer data reports, user interviews, and retail visits to support and build an understanding of “automotive culture.” The team identified two target user groups and defined target audience needs.

Phase 1 – Ideation

A wide array of ideas covering a range of functional package themes and architectures were sketched, with a focus on maintaining the “core equity” of the Turtle Wax brand as well as improving the entire product experience. Starting with retail merchandising, the team incorporated locator pins into the top and bottom of each container so that product facings were aligned. Perhaps most important to the end user, the opening and closing of the container was simplified to greatly reduce the chances of accidental opening and spilling.

Phase 2 – Evaluation

After the sketch concepts had been vetted with consumers, preferred concepts were built in CAD and modified for operational constraints. A range of prototypes were created for additional consumer testing, starting with photo-realistic renderings and ultimately leading to full appearance prototypes.

Phase 3 – Refinement

Once a preferred solution had been identified, design and engineering teams worked hand in hand to tackle the technical challenges of the four-component assembly. This included several rounds of functional prototypes and refinements to unit-cavity tooling of the jar and snap-on overcap.

Phase 4 – Preparation

With the same design and engineering team as well as the manufacturing partners selected in Phase 2, lead times and launch dates were seamlessly aligned with machine platforms and schedules on two continents. Although the two custom injection-molded components were made across the ocean from the jar, the package quickly proceeded through the filling line trials and production sample approvals.

Phase 5 – Production

Production ramped up smoothly. Design elements – notably the proprietary twist-open, locking mechanism engineered to ensure that the package stays neatly sealed and stacks properly on shelf – worked as planned. The shipper carton was modified to achieve tighter packout per carton and more cartons per pallet, which lowered freight costs.

The new Turtle Wax package entered the market in 2010, and the results have been excellent. Unit sales increased immediately and continued to climb, with increases at both the six-month and one-year reporting periods. Ultimately, the improved shelf presence and optimized overall packaging costs have significantly contributed to Turtle Wax’s bottom line. In addition, the new package has been featured in a variety of industry publications and has won design awards.

Anticipate Bottom-Line Results

Ultimately, a strong design process – and a world-class design partner – will deliver results. There are many possible metrics to track, depending on the specific situation. Some options include:

- Higher revenue: more SKUs slotted, more shelf facings, higher consumer awareness, more consumer trial, better consumer engagement (higher loyalty scores and greater share of wallet and more frequent purchases), and higher realized pricing.

- Lower expenses: lower piece cost (less material, less scrap, better manufacturing efficiencies), lower freight costs, reduced inventory, fewer returns, and fewer advertising and promotion dollars (because the product can speak for itself on shelf).

- Product reviews and positive press: accolades from consumers, media, and industry publications.

These metrics should be discussed at the beginning of a design process and measured once the product rolls out. If you have followed the guidelines outlined above, you should have a substantial return on investment that more than justifies the redesign.

Spotlight on Studio One Eleven

Studio One Eleven is the design and marketing services division of Berlin Packaging, a leading supplier of rigid packaging.

Studio One Eleven has deep experience in brand strategy, visual branding, and structural packaging design for customers across virtually every industry. Every engagement starts with a Phase 0 assessment of the market and the consumer with clear goals for success, and continues with support through Phase 5 to ensure manufacturability and functionality of all design elements.

What sets Studio One Eleven apart from other design firms is the lack of large design fees. Customers get the benefit of a world-class team of designers, strategists, and engineers in exchange for purchasing the resulting packaging solution through Berlin Packaging. Because Studio One Eleven is rewarded when Berlin Packaging sells packages, the team is solely fixated on the success of their designs in the market rather than packaging awards or billable hours.

The result is a powerful, self-reinforcing design system – with aligned incentives, an end-to-end process, and demonstrated results.

Getting Started

Designing a new product or redesigning an existing offering can be thrilling when done right. While it’s a complex process, there are three questions that can help get you started.

Why is design helpful for me?

You must understand the category, consumer, and competitive dynamics of your category. Look at examples of how design is helping brands and companies thrive (or hurting brands that do it poorly) to gain insight into the value of a strong package in driving competitive advantage.

When should I use design as a tool?

You need to read the pulse of your brand – is it looking stale, is it losing share, is the category changing? Some companies need help with this decision, as they either don’t have the expertise or the objectivity to make the decision on the role of design. You can use the Package Design Benefit Calculator to build a rough business case for new design. (To download a free copy of this calculator, visit BerlinPackaging.com/DesignCalculator.)

Who can help me?

You can choose from a wide array of partners. Design consultancies can be good at Phases 0 and 1 of the six-phase process outlined above, but they do not perform well in Phases 2 and beyond. Manufacturing firms’ design groups can be good at Phases 3 through 5, but they do not usually have the degree of creativity and breadth of solutions that can excite a market nor the incentive to propose designs that they cannot manufacture themselves. Hybrid design/packaging supply companies provide expertise in all six phases, an unlimited range of manufacturing options, and (in some cases) design services provided at no charge in exchange for packaging business. Select the partner that best complements your strengths and weaknesses.

Summary

Package design is often challenging to execute well. There are many pitfalls that companies can encounter. Indeed, attempting design with improper preparation and a disjointed process can lead to higher complexity, higher costs, lower margins, and disengaged customers and consumers. A robust approach – one that promotes success – honors four imperatives. First, don’t design on a whim. Start with a keen insight into your marketplace and brand and with a set of clear goals you hope to accomplish with design. Second, pick a design agent that has aligned incentives. It usually makes sense to engage a design consultant, but many of them have incentives in conflict with your own, so this choice must be made carefully. Third, embrace a complete, end-to-end process. We outlined a six-phase process that balances divergent and convergent thinking. Each and every stage is critical to success. Finally, anticipate bottom-line results. In today’s competitive marketplace, companies want and need to use design to gain market share and deliver financial returns. Taken together, these four imperatives establish a road-map for getting winning designs into the market while minimizing missteps and pitfalls.