Contact Us | 1.800.2.BERLIN

Supply Chain Consolidation: Rationalizing Packaging Complexity for Profit

Complexity is a major issue for today’s business leaders. In a recent Bain & Company survey of more than 1200 global executives, 63% of respondents claimed that excessive complexity was raising costs and hindering growth.

Properly limiting complexity can have measurable benefits. Southwest Airlines grew up with a very simple business model; it served only secondary airports, with no travel agents, no assigned seating, and only one type of plane (Boeing 737s). This approach reduced or eliminated many of the costs traditional carriers incur and allowed the business to run exceptionally efficiently. As of 2012, Southwest had delivered profitable performance for 40 consecutive years, remarkable in the airline industry. Southwest offers a superior customer experience and is regularly recognized on Fortune Magazine’s list of Most Admired Companies.

Complexity abounds in supply chains. Companies often find themselves grappling with multiple sources for raw materials, variants of items and products, diverse manufacturing and assembly technologies, and widespread distribution networks and fulfillment partners.

This paper looks at ways to simplify and consolidate supply chains with the aim of improving efficiency and profitability. We will address four major questions:

- WHAT: Types of consolidation

- WHY: Benefits of consolidation

- HOW: Approach for packaging consolidation

- WHERE: Sweet spots and balancing acts

The discussion will be centered on packaging-related complexity, but the themes are easily applied to other products, components, and systems as well.

WHAT: Types of Consolidation

Complexity can develop almost anywhere. It also breeds on itself; complexity in one area begets complexity in another, creating an increasingly tangled web of processes and procedures. A simple way to see through this maze is to look through three lenses for potential consolidation.

Suppliers

Who is supplying the raw materials or components? For any given item, you may find that multiple suppliers are playing a role. For commodity items, a program of diversified “spot buys” usually underperforms a well-planned buying program. And specialized items are often sourced from “specialized” suppliers, who are often more narrow than they are special.

Suppliers can be consolidated by first evaluating them according to their capabilities (offering, quality, service, pricing, capacity) and then by negotiating supply agreements with those best suited to your needs.

Items

How many items, SKUs (stock-keeping units), or product lines do you have? Visit your local drugstore and look at the toothpaste section. Crest has over 35 different items. Colgate has its own vast offering. In the drinks aisle, Gatorade has dozens of flavors. The story is the same in pet food, chewing gum, and laser printers.

While much of this complexity is a result of well-intentioned efforts to meet market needs, consumers and retailers alike are weighed down by the options. Items can be consolidated through assortment optimization (evaluating SKUs on a series of strategic and financial dimensions and choosing the items that score best overall) and through standardization (harmonizing items with similar formulations, packaging, or branding).

Infrastructure

What infrastructure do you have to support your operations? Companies invest in assets and systems to manage and grow their business, but much of this infrastructure may be a candidate for consolidation. For example, who is holding inventory in the supply chain? An efficient supply chain will have one expert holding unfinished goods and one expert holding finished goods. If too many players are holding inventory, too much cash is being tied up, leading to higher expenses and inefficiency.

Each element of the operation should be assessed to determine whether it is an essential part of your competitive advantage. If it’s not essential, the business model itself can be consolidated by outsourcing that particular process. P&G’s core competency is in marketing and brand management, for example, so manufacturing and logistics can be outsourced to qualified partners without losing the company’s competitive edge.

WHY: Benefits Of Consolidation

Reducing complexity and consolidating a supply chain takes effort and courage. But the benefits can be many, including:

Purchasing Scale

With fewer suppliers and fewer items, the volume for the average supplier or item increases. This added scale leads to more negotiating leverage and lower costs, or stable costs with higher levels of service.

Infrastructure and Materials Flow

With less supplier and item complexity, the operations and infrastructure needed to support the business can be streamlined. Manufacturing plants will face more stability, which will help with materials management, planning, machine maintenance, and up-time. Sourcing is simplified with fewer different buys to manage. Inventory levels decline and turns improve with fewer different SKUs on the floor. All of these improvements support expense and capex reductions; you can enjoy more efficient plants, less capital tied up, and fewer people required to run and administer manufacturing and materials.

Quality

Smoother operations lead to fewer quality problems as well as lower costs related to poor quality. These avoided costs include both internal costs (e.g., scrap, rework, and overtime) as well as external costs (e.g., recalls, warranty, and brand impairment).

Branding

With fewer items and more reliable products, brands get stronger. Eliminating complexity allows companies to communicate cleaner messages, and shelves look less cluttered with better brand-blocking. This drives consumer engagement and lifts volume.

Management Focus

Complexity swallows up time. There are more things to measure, manage, and document. So removing complexity frees up time for leaders to focus on growing the business.

Companies that attack complexity can see costs decline as much as 25-35% while also seeing revenue lift.

Case Study: Learning From The Model T

The Ford Motor Company has seen the full spectrum of complexity. Managers can learn a lot about the benefits of consolidation by examining Ford’s experience.

The Ford Fusion – one of the leading global automobile platforms over the last decade – has over 15 billion build-combinations in Germany. This is a result of the multiplicative complexity of one body style, seven possible power trains, 179 paint/trim permutations, and 53 factory-fitted options. This is a far cry from the days of the Model T Ford, when the company was ruled by Henry Ford’s sentiment that “[a] customer can have a car painted any color that he wants so long as it is black.”

That contrast has led business consultants to recommend a “Model T analysis” to help companies zero-base costs. This means: what would your system look like – and how much would it cost – if you made only one core SKU? (For Coca-Cola, it might be a 20oz PET bottle of Coke Classic. For Subway, it could be a foot-long tuna sandwich on wheat bread.) You would still need a supply chain, a factory, a distribution network, and sales and marketing functions, but simplifying each of these operations would lower costs.

The goal is not to implement a zero-complexity solution. Indeed, for almost every company, a “Model T” solution would give up too much product appeal and volume. Costs must be balanced against the true needs and wants of different customer segments. But the exercise helps an organization measure how much complexity and variety is necessary in its business. Model T analysis sets a baseline off which the costs and benefits of product changes and diversification can be evaluated. To learn more about Model T analysis, refer to Innovation Versus Complexity in the Harvard Business Review (reprint R0511C).

HOW: Approach for Packaging Consolidation

Consolidation requires thoughtful planning and careful execution. The steps below suggest a high level approach for consolidating packaging.

Engage a Team

Packaging is such a fundamental part of a company’s offering that many functions have a say in it. As a result, a successful initiative to reduce complexity needs to include a broad, cross-functional team. Each person on the team brings a different perspective, and these conflicting points of view need to be addressed through the process. For example:

- Supply Chain: “I don’t want to give up my flexibility in choosing our suppliers and partners.”

- R&D: “Reducing complexity compromises my innovation roadmap.”

- Marketing: “I need to give the consumer what she wants. Yet I appreciate the need for brand simplification and resonance on shelf.”

- Sales: “I need to meet channel needs; I want to have the right product for the right customer. Yet my bag of products is getting too full, and it’s hard to know what’s best for what situation.”

Depending on the company, the team could be larger or smaller. It often makes sense to include the forward-thinking incumbent suppliers, as they can come in with fresh perspectives that are unencumbered by company politics. Teams can then rationalize complexity with an open and honest dialogue where biases are set aside and data are embraced.

Qualitatively Review Complexity

Smart consolidation begins by interviewing all the people who touch packaging. From the packaging designers to orderers to receivers to filling-line personnel and beyond – every person in the chain should comment on the current packaging situation. The discussions should touch on:

- What you buy: The breadth of components, the quantities involved, and the number of suppliers.

- How you buy: The frequency of packaging purchases, the pricing received, and the performance of the suppliers.

- Production issues: The line speeds, fill rates, stability and quality issues.

- How you compete: The competitiveness of your products, consumer and customer reactions, the strategic role of packaging for a product, and key trends to address.

Discussions on these topics can be varied and deep. This process will identify two types of learnings. First, you will surface specific pain points; these are real problems that packaging complexity is creating today. Second, you will create the profile for an ideal packaging situation. This will include the right kinds of suppliers, the right kinds of products, and the right kinds of business models.

Quantitatively Assess Packaging

The qualitative assessment just described will highlight areas of opportunity. These can be augmented with a quantitative review of packaging. This can cover:

- Item attributes: Looking at the specifications of each packaging component raises options of what similar items can be consolidated and what new designs could replace multiple components.

- Item costs: Measuring the piece-price of each component identifies opportunities for immediate cost savings (through supplier consolidation) or helps set targets for renegotiations or supplier requirements.

- System costs: Assessing the follow-on costs of packaging – such as the costs of poor quality, holding inventory, freight, and administration – will help demonstrate the total cost of complexity and areas on which to focus.

This approach will identify an array of hypotheses for complexity reduction. The team can then evaluate these ideas and select the ones to pursue. When done properly, this process can be detailed and time consuming. Some companies turn to consultants and supply-chain partners to expedite the analysis.

Spotlignt on Berlin Packaging

Berlin Packaging is a leading supplier of rigid packaging and has a long track record of helping companies simplify their supply chains.

Berlin has been able to reduce costs for its customers by consolidating:

- Packaging manufacturers utilized – enhancing buying scale on an item-level as well as leveraging Berlin’s overall buying scale.

- Packaging items and components – assessing product, category, and competitor dynamics to deliver less-complex solutions while still maintaining brand integrity and differentiation.

- Packaging inventory to Berlin’s warehouses – freeing up the customer’s physical space and cash flow.

- Freight and logistics – ensuring reliable supply to the filling lines.

Berlin Packaging has a consulting division, E3, which regularly performs these analyses and provides advice to help reduce packaging complexity.

Barr logoOne example involved WM Barr, a leader in household and industrial cleaning with brands including Goof Off, DampRid, and Jasco. WM Barr had over 40 packaging suppliers and slow-turning inventory of over 100 containers and closures. Berlin Packaging carefully assessed consolidation options – factoring in brand needs, filling requirements, and consumer-usage factors – and identified less-complex solutions that generated a direct piece-price save of more than 10%. In addition, by consolidating WM Barr’s inventory, Berlin was able to significantly boost the customer’s inventory turns and reduce administration costs, creating additional savings.

WHERE: Sweet Spots and Balancing Acts

Supply chain consolidation can unlock savings, but it must be done carefully. Some complexity is necessary to compete effectively, so you must balance consolidation with market and organizational realities. Consideration needs to be given to:

Innovation Appeal with Consumers

Consumers are diverse, so important variations must be offered to appeal to them. There are different deodorant brands for males and females, each of which has unique scents, properties, and methods of application. P&G would sell far less deodorant with a one-smell-fits-all approach.

Channel Requirements

In order to get slotted on shelf, retailers and entire channels may require variants. For example, Aquafina offers a special 35-count case for Sam’s Club that is not available to other channels.

System Stability

Consolidation can create risk in a supply chain. In addition to the market and channel risks described above, operational risks can arise by consolidating to an unqualified supplier, for instance. Supply chain leaders can simplify smartly with thorough evaluations of suppliers and having a pre-qualified backup supply.

Organizational Nimbleness

A culture of high standardization and low complexity requires central decision making. But central decision making is slow and can lead to missed opportunities. So, for example, a plant manager is best able to order the right maintenance supplies for his facility, but he may not be securing the lowest costs. Is it better to slow him down and get better piece prices?

In all of these areas, the trick is finding the sweet spot. You want to allow some of this complexity, but only as much as is supported by a business case. In addition, supply chain consolidation touches many functions. Unless every person agrees with the business case and recommended actions, complexity will remain. There is no crystal ball; teams need to come together with a combination of art and science to decide the right level of complexity to keep and the best way to consolidate the rest.

Getting Started

Removing complexity starts with three steps.

First, have a mindset of bold change. Complexity reduction opens up discussions on the fundamental business model and product offering of an organization. For that reason, approaching supply chain consolidation like a Six Sigma “optimization” opportunity is a mistake. Six Sigma is appropriate for fine-tuning processes and finding local optima. But this mentality is too micro at the outset of a complexity-reduction project, where you are seeking new, global optima. Having a compelling target – like reducing the number of suppliers by 50% or trimming product cost by 20% – will reinforce the bold mindset.

Second, form a cross-functional team. As outlined in the How section above, complexity is caused by and touches most functions. So a broad-based team is required and must include change-agents and decision makers.

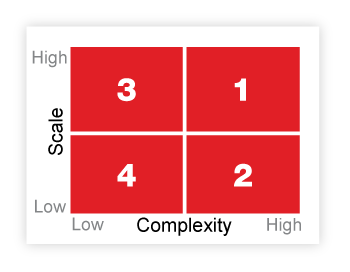

Third, find a target area to consolidate. Conceptually, you can array product lines against two dimensions: their scale (sales, volume, strategic importance) and their current complexity (number of suppliers, number of items/SKUs, impact on assets and infrastructure). There are then two quadrants to contemplate:

- Quadrant 1: high complexity and high scale. Products in this area are high opportunity but also higher risk, given their importance.

- Quadrant 2: high complexity today and moderate/low scale. Many companies start here to build some quick wins. This is where a “tail-spend consolidation” initiative would sit. This type of program looks at rationalizing the many small SKUs and/or suppliers; this tail may represent a modest amount of the total spending but can be a large amount of complexity.

Summary

Complexity burdens most companies. Supply chains suffer from too many suppliers, too many items, and overly-built infrastructures. Packaging is often a large contributor to this complexity. Attacking complexity with a thoughtful consolidation program can yield benefits in packaging costs, infrastructure and materials flow, quality, branding, and management focus. By engaging all the right players, taking stock of the current packaging situation, and thinking differently about complexity, companies can see costs decline significantly while also lifting revenues and profits. Some complexity is necessary, so it’s important to weigh market and operational factors in the process. But thinking through and acting on the What, Why, How, and Where of consolidating packaging complexity will deliver a leaner, more robust, and more profitable supply chain.